In California, employers must provide workers meal, rest, and recovery breaks. Employers that fail to provide uninterrupted, Code compliant meal, rest, and recovery breaks must pay workers premium pay. The California Supreme Court held that such premiums must be calculated at the employee's "regular rate of pay," which is the formula used to determine overtime payments under the state Labor Code.

The California Supreme Court requires employers to provide breaks, relieve employees of their duties during those periods and be sure not to interfere with workers' ability to take breaks. Employers in California can not require workers to remain on duty or "on call" during their rest breaks, according to the California Supreme Court. However, employers are not required to police employees to ensure that no work is performed during that time.

"During required rest periods, employers must relieve their employees of all duties and relinquish any control over how employees spend their break time," the state high court held in Augustus v. ABM Security Services, Inc, 2 Cal.5th 257 (2016).

In light of this ruling, employers should not require or suggest that employees carry company pagers, phones or other communication devices during their rest breaks.

The law currently applies “for each workday that [a] meal or rest or recovery period is not provided,” when an employer fails to provide an employee “a meal or rest or recovery period in accordance with a state law, including, but not limited to an applicable statute or applicable regulation, standard, or order of the Industrial Welfare Commission, the Occupational Safety and Health Standards Board, or the Division of Occupational Safety and Health.

The premium pay provisions largely do not cover overtime-exempt employees. Labor Code Section 226.7(e) provides that they do not apply “to an employee who is exempt from meal or rest or recovery period requirements pursuant to other state laws, including, but not limited to, a statute or regulation, standard, or order of the” IWC. For example, the wage orders exempt executive, administrative, and professional exempt employees from their meal and rest period provisions.

Meal, rest, and recovery breaks do not have the same meaning, these are differentiated by time period, legal code, and length.

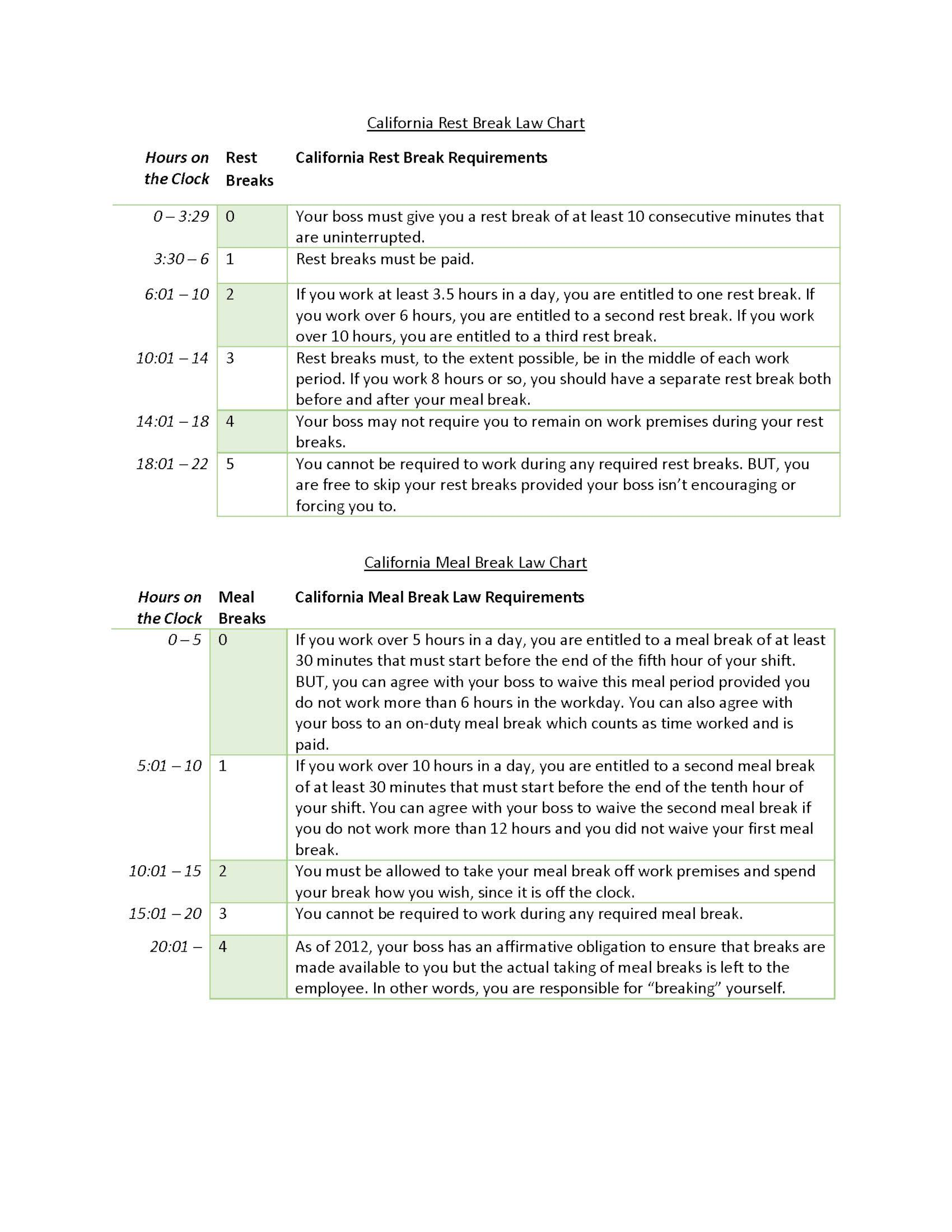

Under California Labor Code section 512, employers must provide California employees with uninterrupted meal periods as follows:

One thirty minute, uninterrupted, unpaid meal break where the employee works more than five hours. Except, the employee may waive their meal break if the employee’s shift is no more than six hours;

A second thirty minute, uninterrupted, unpaid meal break where the employee works more than six hours. Except, the employee may waive their meal break if the employee’s shift is no more than twelve hours.

Under California Code of Regulations title 8, section 11090, employers must provide California employees with uninterrupted, paid rest breaks as follows:

One ten minute rest break per four hours worked. However, the employee is not entitled to a rest break when their total shift is fewer three and a half hours;

Employees working outdoors are entitled to take a recovery break to cool down and prevent heat illness. Employers must allow and encourage recovery breaks, which must be at least five minutes long. The employer cannot require an employee to be on-call during rest and recovery breaks.

When meal, rest, or recovery breaks are denied or interrupted, California workers are entitled to premium pay.

Under California Labor Code section 226.7, if an employer does not provide an employee with a compliant meal or rest break, the employer must pay the employee a premium payment of one hour of pay at the employee’s “regular rate of compensation.” Recently, the issue before the California Supreme Court was whether that premium payment should be calculated using the employee’s base hourly rate or whether the employer must use the employee’s “regular rate of pay.”

In Ferra v. Loews Hollywood Hotel, LLC, 11 Cal.5th 858 (2021), a bartender filed a class-action complaint alleging that her employer failed to properly pay premiums for noncompliant meal and rest breaks because it omitted nondiscretionary incentive payments—such as bonuses—from the calculation.

The trial court and appeals court sided with the employer, finding that the employee's base hourly rate was the proper calculation, but the California Supreme Court reversed and remanded the ruling. The "regular rate of compensation" under meal and rest break rules "encompasses not only hourly wages but all nondiscretionary payments for work performed by the employee," wrote Justice Goodwin Liu in a unanimous opinion on July 15, 2021. Several federal district courts in California to consider the issue reached the same conclusion.

What does this ruling mean? The key takeaway is that employers must calculate premium pay for missed meal and rest breaks in the same way that they calculate overtime pay periods. Furthermore, incentives and amounts other than an employee’s hourly rate or base pay also must be included in calculating meal or rest period premium pay.

Additionally, the ruling is retroactive, which should prompt employers to re-examine past practices in addition to making changes going forward.

If employees do not receive compliant breaks, they are entitled to one hour of pay for each day a rest-period rule was violated and one hour of pay for each day a meal-period rule was not followed. That means workers can receive up to two hours of premium pay per day.

In Ferra, the court concluded that such calculations must include more than just the employee's base hourly rate. The case should remind employers that they should already be paying meal periods and rest breaks for employees that missed these breaks. The court's holding establishes that the amount to be paid for those premiums is not employees' base hourly rate but their "regular rate of pay," which is used to calculate overtime pay and is often higher than the base hourly rate.

According to the California Department of Industrial Relations, the regular rate of pay includes a number of different kinds of non-discretionary payments in addition to hourly earnings, such as commissions, nondiscretionary bonuses and piecework earnings that employees may receive for each unit they produce.

The California Supreme Court provided the following example: Imagine an employee who makes chairs for a furniture manufacturer earns $20 an hour and $10 per piece of furniture produced. If the employee works 40 hours a week and makes 20 chairs, the regular rate of pay would be $25 an hour: (($20 x 40) + ($10 x 20)) / 40.

Note: rest breaks and meal breaks are supposed to be separate, they should not be combined. These do not have the same meaning. Your boss cannot give you a single 1-hour break and say that that counts as all of your meal breaks and rest breaks.

Keep in mind, there are exceptions under California law for certain industries, such as the construction, healthcare, group home, motion picture, manufacturing, and baking industries.

We recommend that most California employers periodically monitor their payroll practices to ensure breaks are being provided properly. If employers become aware of noncompliant breaks, they should determine whether the issue was caused by something in the employer's control, such as the employee's workload, or if the employee voluntarily skipped the break. Employers need to pay the premium if the employee was not able to take a break because of business needs or another employer action. Employers should also consider how the new decisions, such as the rest break premiums in Ferra, will impact their positions in pending meal- and rest-period lawsuits.

Furthermore, rest break premium payments requires the attention of any California employer that pays or is required to pay, meal or rest period premium pay to employees. Employers who do not pay employees any additional pay beyond their hourly pay or any non-discretionary payments equivalent to their employees' regular pay would not have any issue. However, employers who pay additional amounts such as non-discretionary bonuses, attendance bonuses, overtime wages, incentive bonuses, commissions, piece rate pay, or other amounts need to make sure that they pay meal and rest period premium pay at the correct rates.

Employers should be well aware of the need for an employee handbook that includes compliant meal, rest, and recovery break policies. If a handbook has not been updated in years, it may need to be updated with the current state's labor laws. Contact legal counsel at Freeburg and Granieri, APC today to speak with an attorney about compliant employee handbooks and pay period practices.

As an employee, contact legal counsel at Freeburg and Granieri, APC today to speak with an employment attorney about your right to recover premium pay and worker protection.

Our clients become friends, confidants, and repeat customers. Former clients are our best referral source.

Do not be a commodity, find an attorney who treats your legal issue with the care it deserves.