There is no legal requirement in California that an employer provide its employees with either paid or unpaid vacation time. However, if an employer does have an established policy, practice, or agreement to provide paid vacation, then certain restrictions are placed on the employer as to how it fulfills its obligation to provide vacation pay. Under California PTO laws, earned vacation time is considered wages, and vacation time is earned, or vests, as labor is performed.

For example, if an employee is entitled to two weeks (10 work days) of vacation per year, after six months the employee works, he or she will have earned five vacation days. California vacation policies which deny pay for unused vacation days upon termination or force employees to “use it or lose it” are illegal and can carry serious consequences for businesses that employ such policies.

Under the California Labor Code, an employer is not required to provide vacation time, personal days, holiday pay, or paid time off (PTO), but many employers do provide vacation time as a benefit. California employers can generally place restrictions on how vacation time is earned and eligibility for vacation time.

Employers can also impose a waiting period for vacation accrual if you are new, along with accrual caps, as long as the policy is clearly stated.

California labor law states that vacation pay is considered wages that have been earned, but not yet paid. Vacation pay for California employees is offered as additional compensation for services rendered, rather than as a gift or gratuity, and cannot be taken away once earned. Use it or lose it policies that require California employees to use their vacation time or have it forfeited at the end of the year are illegal under California employment law.

Vacation pay accrues (adds up) as it is earned, and cannot be forfeited, even upon termination of employment, regardless of the reason for the termination. (Suastez v. Plastic Dress-Up Co., 31 Cal.3d 774 (1982))

Francisco Suastez, was employed by Plastic Dress-Up Co. (“Plastic Dress-Up”), from October 16, 1972, until July 20, 1978. Throughout this time, and in accordance with its regular policy, the company paid Suastez weekly wages based on his hourly wage. Additionally, it provided certain fringe benefits, including holiday and vacation pay.

The company's vacation policy provided that each employee was entitled to between one and four weeks of paid vacation annually, depending on the length of his or her employment, and that an employee does not become eligible for a paid vacation until the anniversary of his or her employment. Thus, Plastic Dress-Up customarily refused to pay vacation benefits to anyone whose employment was terminated before that anniversary date.

After six years of employment, and before his anniversary date, Saustez’s employment was terminated by Plastic Dress-Up; the said company refused to pay any pro-rata vacation benefits. Suastez then filed suit in the Los Angeles County Superior Court seeking damages, costs and a declaration that the company's refusal to pay him a pro rata share of his vacation pay violated Cal. Lab. Code § 227.3. The trial court held that that Section 227.3 required the company to pay Suastez the vacation pay due him "on the basis of time served."

Unless otherwise stipulated by a collective bargaining agreement, upon termination of employment all earned and unused vacation must be paid to the employee at his or her final rate of pay.

According to California vacation law, employers are permitted to limit the amount of vacation time their employees can earn without actually taking it. An employer, for instance, can implement a policy that only allows their employees to accrue three weeks of vacation time. From then on, workers earn no more vacation days until they take time off from work and use the hours in their vacation bank. Employment policies which place caps on vacation time are legal; employers can stop employees from accruing further vacation, but they cannot take away paid time off which has already been earned.

Although "use it or lose it" vacation policies are not allowed in California, an employer can place a cap on vacation accrual. The California Division of Labor Standards Enforcement (DLSE), the agency that enforces California wage and hour laws, has given some guidance on how the cap should be formulated once a certain level of vacation time periods involved are reached.

While the DLSE previously declared that a cap on accrual must be at least 1.75 times the annual accrual rate, it has since backed off this bright-line rule. Instead, the DLSE simply states that the cap must be "reasonable." It stands to reason that a 1.75 cap is still the most conservative route, but that a 1.5 cap may also be considered reasonable under California law.

Example: An employer's policy provides employees with two weeks of vacation each year. The employer may place a cap of 3.5 weeks on vacation (2 weeks x 1.75 cap). Once the employee accrues 3.5 weeks of vacation, the employee will not accrue any more vacation until he or she falls below the cap.

Employers are also permitted to pay out (or allow employees to "cash out") any accrued but unused vacation time at the end of the year, or another specified time. Because employees are being paid for their earned wages, this type of policy is also perfectly legal.

Employers cannot, under any circumstances, deny employees vacation pay (accrued/unused) if the employee quits, is fired, or let go. All unused vacation time must be paid out upon separation from the company in the employee's final paycheck.

If an employee is fired or otherwise involuntarily terminated, he or she remains entitled to whatever leftover vacation time earnings have accrued at the time of dismissal. By California vacation law, an employer may not withhold unused vacation pay from a departing employee, as these wages are understood as already earned though not yet paid. However, it is legal for California employers to establish probation periods of any length in which vacation time cannot be earned.

If an employer offers PTO, California law mandates that employees get to keep their earned vacation days forever. Earned vacation days never expire in California, and employees are entitled to cash out any unused vacation time when the employee leaves the company.

(1) Restrictive Vacation Policy: California law requires employers to let employees bank accrued vacation pay, but it doesn’t place many other limits on employers’ PTO policies. For example, employers can require that employees give several weeks notice before taking an advanced vacation day.

(2) No PTO Pay-Out with Final Paycheck: When an employee is terminated or quits, California law requires employers to issue a final paycheck within a specified time period. This final paycheck must include a payout for all unused vacation days.

(3) Taking Away Vacation Days: Under California labor law, an employer cannot take away your vacation days as a punishment. Once you earn a vacation day, that day is treated as equivalent to a day’s worth of wages. Employers can, however, count partial-day absences against vacation time. For example, if an employee takes an extra four hours for lunch, an employer can typically count that as using half a vacation day.

(4) Independent contractors: Employers often try to avoid giving workers the protections of California labor law by misclassifying them as independent contractors. But California imposes hefty penalties for misclassifying workers as independent contractors to avoid giving them the rights due to employees. If you’re an independent contractor and your contract with the company gives you paid time off, this fact makes it seem that you should be an employee because your employer has the right to control your hours.

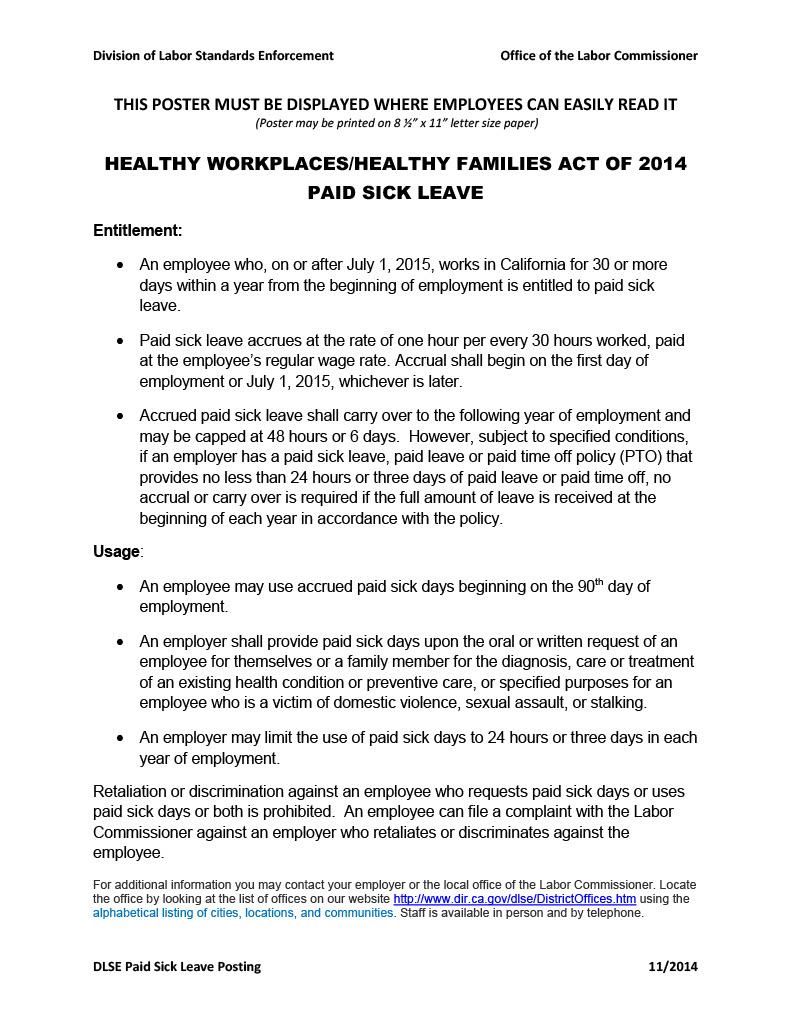

Sick pay is not considered vacation time in California and therefore not subject to these rules. If an employer has a stand-alone sick leave policy, sick pay does not need to be paid out upon separation from the company.

However, if your employer lumps both paid sick days and vacation time together into PTO, then all of the PTO time is treated like vacation time.

Similarly, holiday pay for fixed holidays, such as New Year's Day or the Fourth of July, are not considered vacation and do not need to be paid out on separation. However, "personal days" or "floating holidays," which are not tied to any specific day and can be used by employees whenever they wish, are treated as vacation and are subject to the same rules.

No, such a provision is not legal. In California, vacation pay is another form of wages that vests as it is earned (in this context, "vests" means you are invested or endowed with rights in the wages). Accordingly, a policy that provides for the forfeiture of vacation pay that is not used by a certain date ("use it or lose it") is an illegal policy under California law and will not be recognized by the Labor Commissioner's Office.

Yes, your employer has the right to manage its vacation pay responsibilities, and one of the ways it can do this is by controlling when vacation can be taken and the amount of vacation that may be taken at any particular time.

Under California laws, unless otherwise stipulated by a collective bargaining agreement, whenever the employment relationship ends, for any reason whatsoever, and the employee has not used all of his or her earned and accrued vacation, the employer must pay the employee at his or her final rate of pay for all of his or her earned and accrued and unused vacation pay (California Labor Code Section 227.3). Because paid vacation benefits are considered wages, such vacation pay accruals must be included in the employee's final paycheck.

If you believe that your current or previous employer may be in violation of California labor laws regarding vacation pay, PTO, holidays, or sick pay; you may want to contact a California labor laws attorney.

You can sue your employer in California courts for unpaid vacation time in a wage claim. It is illegal for an employer to take away vacation time or refuse to pay employees for unused vacation time (a PTO cash-out) after you leave the company.

Ideally, you want to contact a law firm or attorney advertising free evaluation of your vacation time and vacation policies. For the privileges of an attorney-client relationship to protect your sensitive or confidential information, contact the law firm of Freeburg & Granieri for an assessment of your employment law case.

Our clients become friends, confidants, and repeat customers. Former clients are our best referral source.

Do not be a commodity, find an attorney who treats your legal issue with the care it deserves.